Fictional Documentarism : An understudied genre in Danish and European Literature

1The Danish author and museum director Peter Seeberg (1925-99) devised and developed from around 1974 until 1990 a remarkable genre of fictional short prose, which has not attracted as much international attention as it deserves. Seeberg himself labelled this genre “fictional documentarism”, yet sometimes he also simply called the texts “lists”.1 The texts are far from always presented in list form in the strict sense of the word (yet they can indeed be so). Often, they are lists in a broader and perhaps more metaphorical sense. They are highly diverse but they all, in different ways, engage with non-literary, nonfictional types of texts that the author may have encountered in his museum work, or just in his daily life. For example, last wills and testaments, obituaries, genealogies, graveyard registrations, hotel guest books, cookbook recipes, or railway station announcements.

2The purpose of this paper is to discuss the genre of fictional documentarism. I begin by briefly introducing Seeberg and tentatively defining the genre. Then, I present and consider three of the author’s most characteristic fictional documentary texts before I compare the genre to several examples from 20th and 21st century European literature. After this, I turn to a theoretical implication showing how attention towards this understudied genre can serve as a means to highlight and evaluate differences between two conceptualizations of pseudofactuality. Lastly, I conclude by arguing how fictional documentarism, despite its engagements with the nonfictional, often creates impossible situations in order to point towards its fictional status. My scope with the paper is thus both theoretical and practical, insofar as I both endeavour to define and discuss an understudied genre and its implications and to present some short readings of Seeberg’s texts.

Peter Seeberg and the genre of fictional documentary

3Peter Seeberg is a major figure in modern Danish literary and intellectual history. His literary works are relatively few. The most canonical of his fiction works count only four novels and six collections of short prose apart from children’s books and a few plays. All these works, however, are highly acclaimed in Scandinavia. During his lifetime, Seeberg was awarded close to every domestic literary prize, and at least some of his books are widely translated. The novel Hyrder (1970, “Shepherds”), for example, is translated into nine languages, including French, German, Russian, Polish, and Finnish. Unfortunately, only a few of his texts are published in English, yet translations of more of his works are either planned or on the way.2

4For almost the entirety of Seeberg’s unusual literary career, he worked full-time in museum research, dissemination, and administration. After obtaining a Master of Arts degree in General and Comparative Literature from the University of Copenhagen in 1950, he was for some years affiliated with the Danish National Museum. 1957-58 he was with the Hanseatic Museum in Bergen, Norway. Later in 1958, he moved back to Denmark and was for a short period employed at Aalborg Historical Museum before, in 1960, he was finally appointed director at the regional Viborg Museum in the western part of the country – a position he held until his retirement in 1993. Despite Seeberg authored only a relative few works of fiction, he was very productive as a nonfiction writer. His nonfiction counts approximately 500 journal or newspaper articles and books, mostly written in connection with his museum activities.

5Amongst the most interesting aspects of Seeberg’s oeuvre is the way his nonfiction was influenced by his fiction and, vice versa, the ways his fiction was influenced by his nonfiction. An example of the latter are the texts that I, using the author’s own term, call “fictional documentarism”. These texts are fairly evenly distributed throughout four of his late collections of short prose : Dinosaurusens sene eftermiddag (1974, “The Dinosaur’s late Afternoon”), Argumenter for benådning (1976, “Arguments for Pardon”), Om fjorten dage (1981, “In Two Weeks”), and Rejsen til Ribe (1990, “The Journey to Ribe”). He also published a final collection, Halvdelen af natten (1997, “Half of the Night”), but here the genres are somewhat different.

6Seeberg did not provide any formal definition of fictional documentarism. I will propose a tentative definition, namely that : Fictional documentarism is a genre of fictional texts that mimic or in other ways play with non-literary, nonfictional text types most often written documents. What the fictional documentary texts seem to have in common is that the texts they mimic or play with are texts that ordinary people may encounter in their daily lives and that they may sometimes even produce examples of themselves. The fictional documentary texts can be in list form in the strict sense of the word but, most often, they are not. They can be highly narrative, or they can be hardly narrative at all. Leaving out for now the otherwise important discussion of whether narrativity is a prerequisite for fictionality, I call them all fictional.

Three examples

7Seeberg’s fictional documentary texts are, admittedly, very heterogeneous. Some appear at first glance purely documentary, others are very obviously fictional. I shall present three examples that indicate the diversity. My first example is a purported line of descent titled “Genealogy : Male Line”. I quote the initial lines :

1) Thorbjørn Hvidsten, born 27 March 1933 in Horsens, son of 2) and wife 2)1, Upper Secondary School Certificate from Horsens State School 1951 (natural sciences), graduate from college of dentistry June 1956 (distinction), practice in Vildbjerg, Ringkøbing County from August 1956, married 19 June 1957 to dentist Jytte, born 9.10.1934 in Hanstholm, Hansted Parish, Thisted County, daughter of fish importer Kristian Sommer, b. 23.12.1904 and wife (m. 9.12.1933) Dagmar Hundborg, b. 24.6.1912. Children : 1. Per, b. 7.4.1959, 2. Hans, b. 16.4.1961, 3. Kristian, b. 6.12.1962.3

8What we see here is the first entry of a long list of laypeople (or laymen, since the text only presents the male line). The text describes a dentist who was married and had three sons. It is, in the most characteristic sense of that word, ordinary. The personal names are North Germanic or North Germanic variants of Latin or Greek names. They are generally typical for the time, yet not overly common or stereotypical. The place names are all referring to real places in central or northern Jutland, the provincial Danish mainland. There was actually a school called Horsens State School at the time, and fishing and fish importing was actually the major trade in Hanstholm, Hansted Parish.

9After having described the life of the dentist, the list continues in reverse chronological order with the lives of his ancestors for nearly five pages without much going on. The people whose lives are listed are described so unassumingly that it is hard to believe that the text is in fact invented. It is, nevertheless, important to stress that the text is not nonfictional in any recognized sense of that word. Yet had it not been printed in a volume of fiction, one would probably have believed it to be an example of nonfiction.

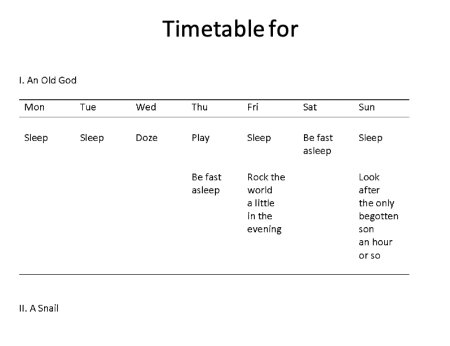

10More obviously fictional is my second example. It also relates to the concept of the ordinary but in a different way. The text titled “Timetable for…” plays with a well-known everyday text type, namely the weekly timetable. The content, however, is by no means ordinary, or perhaps it is ordinary in an extraordinary way.

11The text is a satirical account of what an old, non-interventionist god might be doing during the seven days of a week. Like in “Genealogy : Male Line”, nothing much is going on. The old god mostly sleeps, sleeps, and dozes. Friday, he rocks the world a little in the evening, and he only finds time to look after the only begotten son for an hour or so on Sunday.

124 What makes the text hilarious is, arguably, the way it juxtaposes the God’s time and earthly time. It obviously plays with the myth about God creating heaven and earth in seven days according to the first Genesis in the Old Testament. Yet since then, after having fathered the only begotten son, God has apparently grown old, and his weekly schedule now resembles that of a retired human being living in a heavenly – or perhaps rather in an earthly – state of idleness. God’s only duty is to take care of Christ who might have left home at some point but, probably after the ascension, seems to have moved back in (the last part of the text, printed underneath the timetable for the old god, shows the weekly tasks for a snail. This most earthly creature has, as it appears, no schedule and hence no duties whatsoever).

13My third example is characteristic of the way that Seeberg’s fictional documentarism sometimes engages with well-known nonfictional text types in other ways than mimicking. The text is titled “From the guest book : (Provincial hotel, approx. 30 km from Copenhagen)”. It consists of 12 short narratives about extraordinary events, which over the years have taken place in an otherwise ordinary Danish hotel. One of them reads :

Peter Petersen, a businessman from Lolland, comes one evening in the mid-1930s asking if we have oysters. Yes, we surely did. He gets 12 oysters and a bottle of champagne, a little too much perhaps. He seemed to be enjoying it, as far as we could tell, he was smiling at us. Then he goes up to his room. The next day we have to break into his room when they phone him from home. He had hanged himself in the bathroom. It was quite new then. He had gone bankrupt.5

14What is striking here is the lack of coherence between the title and the main text. Seeberg is certainly not trying to mimic the style of a businessman from the province of Lolland writing his story in a hotel guest book. The businessman is, after all, highly unlikely to have composed the story – for several reasons, one of them being that he is dead. Yet also, the halting oral style of discourse is hardly compatible with a businessman’s writing. The diction is dominated by alternations between past and historical present (“He seemed to be enjoying it […]. Then he goes up to his room”), free indirect discourse (“Yes, we surely did”), and inappropriate and involuntarily funny impulsive insertions (“He had hanged himself in the bathroom. It was quite new then”). The most notable reason why this narrative could not be a note in a guest book, however, is that it is written in the second person plural.

15If we want to maintain that the title is meaningful, the text’s position of enunciation can be attempted naturalized by picturing the hotel manager or a chambermaid leafing through the guestbook while adding what he or she has witnessed during the years. Yet this naturalization is hard to maintain. The fact that the earliest stories of the text take place around 1900, and that the time of enunciation likely equals the time of writing, would make the manager or the maid unbelievably old should he or she have experienced all the events. It is arguably more reasonable to assume that Seeberg is not mimicking a realistic narrative situation but is playing with a nonfictional text type by creating an impossible fictional documentary story. It is rather as if the spirit of the hotel were reading aloud from its own imaginary records, so to speak.

Fictional documentarism and European Literature

16Peter Seeberg is one of a kind in Danish literature. His style of writing has influenced the following generations of writers in several ways, but his genre of fictional documentarism has neither any direct domestic predecessors nor successors. Despite the uniqueness of the genre in Denmark, it might be fruitful to compare it to a number of examples of European literature from the 20th and 21st centuries.

17The French historical avant-gardes of the beginning of the 20th century make an obvious early point of comparison. Due to their exploration of the frontiers between the literary and the non-literary as well as between fact and fiction, the historical avant-gardes challenged the notion of the ordinary in ways not quite equal but still comparable to Seeberg’s practice. A well-known example of this challenge is the literary use of the “fait divers” (i.e., ultra-brief news stories from the French daily press, often narrativizing ordinary events).6 They were either printed as ready-mades or processed and integrated into literary works. Examples are numerous : Pierre Naville, Benjamin Péret, and later André Breton transcribed several of these short news articles from newspapers and published them throughout their journal La Révolution surréaliste from the first issue in 1924. Also, André Gide is known for having transcribed a large number, some of which were integrated into his novel Les Faux-Monnayeurs (1925), and many were published in the journal Nouvelle Revue Française from 1926 to 1928.

18What the historical avant-gardes’ use of fait divers has in common with the genre of fictional documentarism is their way of expanding the domain of the ordinary to encompass the extraordinary. Dominique Jullien contends that fait divers are stories “about little people made big by publicity or the press” (Jullien, 2009, p. 66). This is not far from what Seeberg often explained as being his ambition in his literary writings. “[To] me, much of a writer's work is to be dealing with people who do not know that their lives are worth anything and make it clear through literature that they are”, as he puts it in an interview.7

19A pronounced difference between the historical avant-gardes’ use of fait divers and the genre of fictional documentarism is that the fait divers are most often, if not always, authentic documents whereas fictional documentarism consists of non-authentic or what Alison James calls “created” rather than “found” documents (James, 2020, p. 79). Therefore, fictional documentary texts are not ready-mades either. Seeberg’s texts may in some cases appear very documentary in their style of writing, as we have seen in his “Genealogy : Male line”, or they may appear very obviously fictional, as we have seen in his “Timetable for…”. Yet the texts are in my view all fictional. They tell about invented events – or a combination of invented and real events – and they are printed side by side with more traditional fictional narratives in volumes of which three out of four bear the subtitle “Noveller" (Short stories).

20The literary use of the fait divers is a practice different from fictional documentarism but with a common point of interest in the frontiers between the fictional and the nonfictional, the literary and the non-literary, and not least between the ordinary and the extraordinary. More regular examples of fictional documentarism can indeed be found in writing practices from the historical Swiss and French avant-gardes of the early 20th century to various European postmodernisms and neo-avant-gardes of the 1970s and 1980s as well as in contemporary satirical fictional short prose from 21st century American literature. To mention a few examples : Swiss writer Robert Walser's "Das Stellengesuch" (Kleine Dichtungen, 1914) takes the form of a job application and is probably amongst the earliest examples of fictional documentarism in the previous century. Guillaume Apollinaire's short poem "Carte postale" (Calligrammes, 1918) is of somewhat similar character. The poem reads like a postcard text, and it is visually presented as a postcard with a postmark drawn by hand.

21Famous examples from the 1970s are Polish Stanisław Lem's reviews of non-existent books in A Perfect Vacuum (Doskonała próżnia, 1971) and Imaginary Magnitude (Wielkość urojona, 1973). So are also some of George Perec's quotidian experiments, for example his cookbook recipes "81 fiches-cuisine à l'usage des débutants" (Penser/Classer, 1985). These recipes are genuine in the way that they could, in principle, be followed when cooking a dinner, yet their main purpose is, rather than to teach how to cook, to explore a logical system of combination of everyday elements. Further examples of the genre are not least abundant in early 21st century American literature. Amy Hempel's “Reference #388475848-5" (The Dog of the Marriage, 2005) takes the form of a letter of complaint about a parking ticket, and Namwali Serpell's "Colors / Turquoise : A liberal arts education" (Cabinet, no. 60, 2015) purports to be a college course catalogue.

22I believe that the genre of fictional documentarism, which Seeberg was the first and so far the only one to extensively explore in Danish literature, may be traceable throughout 20th- and 21st-century European literature. Until now, however, it remains largely understudied. This shortcoming ought to be remedied not only because it will unearth a number of interesting texts. Fictional documentarism, I argue, constitutes an intriguing case also because it may call into question some basic concepts of theories of fictionality. In the following, I shall address one of these concepts, namely pseudofactuality in Nicholas Paige’s and Françoise Lavocat’s understandings. I have chosen to discuss these two scholars’ understandings of this particular concept because of its actuality in recent research and because I believe a comparison of the concept to fictional documentarism may be mutually enlightening.

Fictional documentarism and pseudofactuality

23Fictional documentarism, as we have seen, both in Seeberg’s case and in the related European cases, is a genre of fictional texts that mimic or in other ways play with non-literary, nonfictional text types, most often written documents. David Shields and Matthew Vollmer have published a collection of primarily recent American texts, some of which fit my definition, some of which do not. The volume bears the multifaceted title Fakes : An Anthology of Pseudo-Interviews, Faux-Lectures, Quasi-Letters, "Found" Texts, and Other Fraudulent Artifacts. In the subtitle as well as in the introduction to the volume, Shields and Vollmer name their genre by the – as they somewhat admit themselves – not very precise term “fraudulent artifacts” (Shields and Vollmer, 2012, p. 13). Yet they also employ the prefix pseudo- in the wording “Pseudo-Interviews”. It would be tempting to take this wording a step further and characterize fictional documentarism as a type of pseudofactuality. While fictional documentarism does share some features with what in the last decades has been defined as pseudofactuality, it remains in certain respects different.

24Pseudofactuality as a concept is discussed by Nicholas Paige in his Before Fiction (2011) and further developed in his Technologies of the Novel (2021). Paige applies the term pseudofactual to what he calls the early modern regime from approximately 1670 until 1800, a time when it was common for authors to present their novels as if they were true stories. What was new here compared to the previous period, Paige argues, was that novels most often did not contain grand epics about mythological figures or legendary heroes but stories about ordinary people based on purportedly found manuscripts, correspondences, and memoires, or sometimes on purported eyewitness accounts. The pseudofactual regime implied what Paige calls a “pseudofactual pact” (Paige, 2011, p. X). Novels generally pretended to be about real people writing about their own deeds or about real people writing about other real people’s deeds. The tacit agreement was that the readers, in turn, pretended to accept that the characters were true. An important point, however, is that the authors of the time understood this was all just pretence. Readers, most likely, did not really take the truth assertions at face value, and the “prefix 'pseudo'”, Paige has it, “is intended to stress that writers did not intend for their assertions to be believed” (Paige, 2021, p. 22).

25Françoise Lavocat has a broader interpretation of the term. To her, pseudofactuality encompasses literary hoaxes such as Les Lettres portugaises (1669) and Wolfgang Hildesheimer’s mock biography Marbot (1981). Unlike Paige, Lavocat contends that a prerequisite for this kind of pseudofactual texts is that readers trust them, i.e., that there is an “interdependence of truthfulness and readerly belief” (Lavocat, 2020, p. 589). This readerly belief, Lavocat has it, involves a paradox. On the one hand, plausibility is a necessary foundation for us to hold a narrative as true. On the other hand, the narrative must stand out from the ordinary to make us invest our belief in it. Therefore, to be plausible the narrative must also to some extent be implausible. This paradox is seemingly what prompts Lavocat to state as an interesting dictum that, “hero(in)es of pseudofactual narratives are typically situated at the intersection of the impossible and the plausible” (p. 581).

26A main difference between Paige’s and Lavocat’s concepts of pseudofactuality is the level of required belief. Whereas readers of pseudofactual novels, according to Paige, rarely were duped to take the stories for real, pseudofactual texts in Lavocat’s understanding must induce an incentive to believe in them, even if this belief involves a paradox. The two conceptualizations, however, also differ in another and related way. To Paige, pseudofactuality is first and foremost a matter of paratext. The truth claims of the pseudofactual novel normally did not so much lie in the manner of the telling, he argues, as in a declaration in the preface to the novel and/or on the title page. Lavocat, on the contrary, has a broader interpretation also of the literary means. She names three categories of factual signposts, which pseudofactual texts tend to employ : a pragmatic framework of both the paratext and the text itself, generic conventions of factual genres, and stylistics or what she calls a “rhetoric of authenticity” (p. 582).

27Seeberg’s genre of fictional documentarism is neither pseudofactual in Paige’s nor in Lavocat’s understanding of the term. The same applies to the examples of 20th and 21st century European works of literature that I have referred to above. Fictional documentarism does, nevertheless, share some features with pseudofactuality, and what is interesting about it is not least the fact that it cuts across the principal differences between the two understandings of this concept. The attention towards fictional documentarism, therefore, invites us to highlight and evaluate the differences between these two understandings.

28Like pseudofactual novels in Paige’s understanding, fictional documentary texts tend to question the concept of the ordinary, and they are almost always about common people rather than being grand epics about mythological figures or legendary heroes (the rare exception, perhaps, being "Timetable for..." – but even this text, arguably, depicts God and the only begotten son as ordinary people rather than mythological figures). Furthermore, the texts are hardly meant to be believed. This is the case for several reasons, one is that they do not always mimic the kind of nonfictional text types they engage with but sometimes play with these types in other ways such as is the case with the text “From the guest book”. Other times they are simply about incredible, humorous incidents like God spending his old age looking after the apparently still young only begotten son. Another obvious difference between Seeberg’s fictional documentarism and Paige’s concept of pseudofactuality, is also that the documentary air of fictional documentarism does not reside in the paratext.

29None of the examples I have shown are paratextually disguised as nonfiction. They are printed alongside traditional fictional narratives in volumes most often subtitled “Short stories” (and, therefore, they are not hoaxes either). Like pseudofactual texts in Lavocat’s understanding, fictional documentarism employs a broader range of literary means than that of paratext for its documentary similitude. It is always characterized by the second and often by the third of her categories of factual signposts. That is, the fictional texts always relate to nonfictional text types and thereby to generic conventions, and they often stylistically imitate an “authentic rhetoric” of these types such as the dry and factual style of a line of descent.

30Fictional documentarism both resembles and differs from Paige’s and Lavocat’s mutually different concepts of pseudofactuality. As I have shown, a comparison of fictional documentarism to the two concepts can serve as a means to highlight the differences between them. Lavocat’s concept is broader than that of Paige. Yet her insistence on the presence of readerly belief makes her concept unfit for explaining the prototypical pseudofactual novel from 1670 to 1800, which is the subject area for Paige. The question remains, then, whether Paige’s and Lavocat’s concepts are actually so much at odds that they cannot really be said to refer to the same phenomenon.

The impossibility of fictional documentarism

31Towards the end, I want to address another important question, namely how fictional documentarism can relate to impossibility. In suggesting an answer, I will return to Seeberg. The fictional documentary texts I have referred to, in different ways and to different degrees, point towards their fictional status or the fact that they are “created” rather than “found” documents (in James’ terms). Seeberg’s texts generally point towards the fictional by being published alongside more traditional short stories in volumes that most often declare themselves as fiction. Some of them also present impossible positions of enunciation and some play with other kinds of impossibilities such as anachronisms.

32Being a museum director, Seeberg was rather concerned with historical accuracy. He once famously uttered that he did not “care for [authors] who describe a day in 1517 without making an effort to check up on the weather of that day”.8 A fair number of his own texts, nevertheless, do contain historical inaccuracies and anachronisms, and at least sometimes, we must believe them to be intended. This is the case with the text “A Letter on Lead : Composed on the square in front of the cathedral in Viborg on the eighteenth Sunday after Trinity 1247 AD”. It is amongst the last and most elegant examples of fictional documentarism in Seeberg’s oeuvre.

33The short text takes the form of a letter from a roofer to the Danish king. It begins, “I, Laust, son of Gudmund, master of lead roofing, write to you, King Valdemar, son of Canute, as rumour and the assertions of truthful men have it that you are ill, alas that your dying day is drawing near”.9 The roofer now to the readers’ amusement recommends the King to consume lead, which he apparently does not know to be poisonous but trusts can cure the King’s disease. Lead is, should we believe the roofer’s high-flown praise, a panacea. From his own experience, he states :

Regardless of whatever aches and pains I should feel in my loin and limbs, yes in my joints, they vanish in the twinkling of an eye. Is the mind wistful after a dreary and lonely night when womenfolk are not to be had in this town, then jesting and singing break out owing to the brisk effect of the lead […].10

34“A Letter on Lead”, like several of Seeberg’s other texts, plays with the distinction between the ordinary and the extraordinary. The case that the unimpressive, dull-looking lead should have magnificent healing powers, as well as the case that a layman should be able to advise a king, is at the core of Seeberg’s philosophy of life. What only the historically knowledgeable will notice, however, is that the text is fundamentally ironic. The irony of the text is to be found in its subtitle. In 1247, when the letter was purportedly composed, King Valdemar had already been dead for 65 years. The text by this anachronism may make us wonder whether, because of his consumption of lead, the roofer has really not realized that the king has been dead for so long. Yet it may also remind us that it is an artistically produced document.

35To infer that the roofer is so insane that he mentally lives 65 years in the past would be a humorous naturalization of the anachronism. But it is still so highly improbable that we must at least allow for another interpretation, namely that the story is simply impossible. By what we with Lavocat could call the generic convention of the letter as well as by the somewhat “authentic rhetoric” of the roofer’s passionate style of writing, the text points towards the documentary and the plausible. Yet by means of the anachronism, the text points towards its inventedness and the impossible. Consequently, it would, arguably, be more suitable to conclude that not only pseudofactuality in Lavocat’s sense but also this example of fictional documentarism is situated somewhere in the intersection between the plausible and the impossible.